In April 2017, a number of news outlets in the United States and the United Kingdom carried a story of a Mississippi couple undergoing infertility treatments who found out during the process that they were biological twins.

Although several of these news outlets are usually considered to be reliable sources, they were passing along a story that originated on a website for a newspaper that does not exist. The story, and the “newspaper” itself, were fakes.

Ironically, the article managed to spread weeks after “fake news” and “alternative facts” had become hot topics in the 2016 American presidential campaign and the election aftermath.

Despite the current attention, fake news is not a new phenomenon. Thomas Jefferson and John Adams spread rumors about each other in the press in the American presidential campaign of 1800, Holocaust deniers have been around since World War II, and propaganda and disinformation have probably played a role in every war.

Today’s internet makes it easier to get fake news into the public eye and spreads it like wildfire. The social media giant Facebook, considered to be a major, if unwitting, distributor of fake news, is stepping up its efforts to silence accounts spreading manipulated or inaccurate information. Google, whose ubiquitous search engine did not discriminate between real and fake news, has tweaked its algorithms to demote material originating from non-authoritative websites and is asking users to help identify and tag suspect content. Jimmy Wales, co-founder of the crowd-sourced online encyclopedia Wikipedia, is launching Wikitribune, an online news site combining the efforts of paid journalists and volunteer contributors, to counteract fake news.

Project 7 in the Competent Communication manual emphasizes researching your speech topics. Your speeches will be more effective if you support your points with facts collected from reliable sources. “Facts” can include verifiable information and statistics. The internet certainly makes access to materials from organizations and individuals readily available. How can we know what is real?

How to evaluate stories and sources

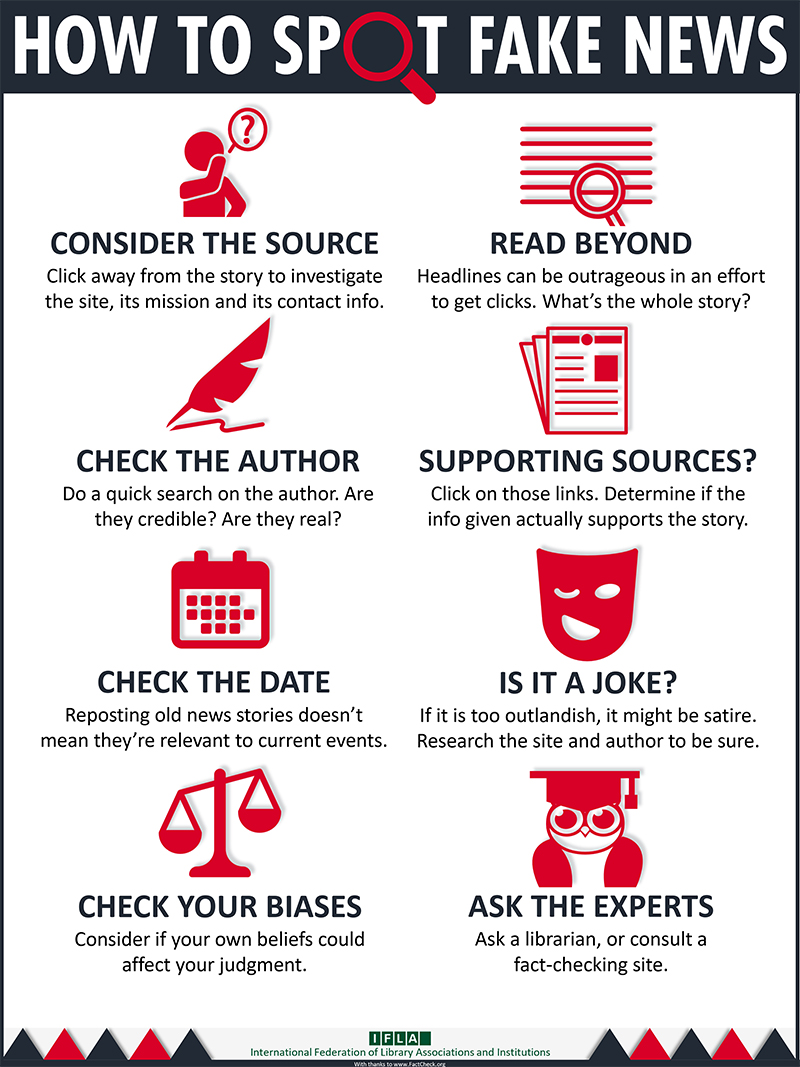

The International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions (IFLA) has a number of suggestions when it comes to evaluating news stories.

- When reading an article you may want to cite, look at the website or publication to see what organization may be behind it. Check out the author as well. Are the other articles found on the same site or by the same author in a similar vein? If supporting sources are listed, it may be worth checking those. If no supporting sources are listed, that may be an indication that something is amiss.

- The headline is not usually written by the author and may not really reflect its content. A headline’s aim is to get readers to read the article, and nothing grabs readers like sensationalism. The article may be meant as a joke or satire. The best jokes build on a grain of truth; don’t assume the whole pile is true.

- Check the date of the story; sometimes it’s really just old news.

- Examine your own biases. Do certain subjects tend to bring you closer to anger more quickly than others? Fake-news writers aim for hot-button issues.

- Quantity does not signify quality; the number of times an article is cited or repeated is not necessarily an indication of its trustworthiness.

In the story of the Mississippi twins, no names were given for the author, the couple involved, their doctor or even the clinic. In short, there were no verifiable details in the story. The article appeared on a website for a newspaper that does not exist, and the website lists no editors or writers. The story was simply a fictional tale on a salacious topic sure to draw attention.

One way to check on a rumor or news story is to consult one of the websites set up to combat fake news. Possibly the oldest is Snopes.com, which began in 1994 as a place to check out urban legends, sensational stories that seem to have a life of their own and pop up every so often. Snopes covers the gamut from today’s political headlines to the Neiman Marcus cookie recipe revenge story that’s been around since at least the late 1990s. The most recent rumors are covered in the Snopes Hot 50 list.

FactCheck.org is a project of the Annenberg Public Policy Center of the University of Pennsylvania. Created in 2003, it concentrates on U.S. politics. It also has a section called SciCheck, which evaluates scientific claims publicized to influence public policy on topics such as global warming, pesticides and drug use.

PolitiFact.com is another site focusing on American politics. It was created by the Tampa Bay Times in 2007 and won the 2009 Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting for its coverage of the 2008 presidential campaign. PolitiFact has sections dealing with specific states in the U.S. and also rates the truthfulness of specific politicians and political commentators.

The U.K.’s Channel 4 News FactCheck, launched in 2005, is credited as the first regular source of political fact-checking in Europe, followed a few years later by similar sites in France and the Netherlands. Some sites are sponsored by newspapers, such as Le Monde’s Les Décodeurs, the Decoders, whose motto is “venons-en aux faits,” or let’s get to the facts. Others, such as Italy’s Pagella Politica, were created by independent organizations.

Today there are 113 independent fact-checking groups active in more than 50 countries around the world, according to a report released by Oxford’s Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism in November 2016. More than 90 percent of these sites were established since 2010.

Nothing is bias-free

There really is no such thing as a totally bias-free publication or website. As objective as an article may appear, the mere fact that choices had to be made as to what to include and what to leave out introduces an element of bias. Many publications do strive to be as bias-free as they can be. How can we tell which ones these are?

When it comes to websites, domain names can give you an idea of potential bias. Most of us are now aware that .gov designates a government-sponsored website, .edu is for an educational institution, .org is an organization, .net is a network and .com and .biz are commercial enterprises. We tend to trust government and educational sites, but it isn’t always that simple. Savvy readers know that a government site may highlight information favored by those who are currently in power, as we are seeing with the elimination of climate change information on U.S. government websites. Websites affiliated with a college or university may not be endorsed by the institution itself; in the past, some individual faculty holding extreme views posted these on their webpages. Although we may feel we are aware of specific biases represented by websites, be aware that look-alike sites with similar web addresses may actually be counterfeit sites attempting to snag readers holding opposite views.

Finding reliable sources

Computerized indexes of magazine and journal articles began appearing in academic and public libraries in the 1990s. Today, you would be hard-pressed to find a periodical index in paper form in a library, and most databases have expanded to include the full text of the articles they index. Many public libraries allow their patrons to access these databases from home, using their library card barcode as a login. In some areas, access goes beyond the local public library and is made available to residents of an entire state, province or county, such as Florida in the U.S., and Quebec in Canada. The periodicals included in these databases are likely to be those that are widely considered to be reliable.

Some of the databases are general in nature, covering a variety of subjects appearing in popular or scholarly publications. Many libraries use a “discovery tool” which allows users to search several databases at once. This one-stop search may be all you need to find material for your speeches. Be aware that not all of a library’s databases may be connected to the discovery tool, and that for some topics, selecting a subject-specific database (like for health or business) would be more useful.

Be aware that look-alike sites with similar web addresses may actually be counterfeit sites attempting to snag readers holding opposite views

EBSCO and Gale are among the most commonly encountered database vendors, but there are many others. Despite specific differences, there are a number of common functionalities across databases. Knowing how they work can help you get more relevant results from your searches.

Try to distill your search down to the most important words. To research the topics in this article, for example, you might focus on the idea of evaluating sources of fake news. You might begin with these search terms: fake news evaluation. Many databases search for a string of words together. If the database uses Boolean operators, the search fake news AND evaluation may return better results. All articles returned by that search will have fake news and evaluation somewhere in the article.

We may want to put fake news in quotes to ensure those words are searched together, “fake news.” This is also useful when searching the titles of specific books or movies, as in “run lola run,” or names of organizations, like “toastmasters international.” Truncation is a way to get all forms of a word. The truncation symbol varies from database to database, but frequently an asterisk is used. If we then run the search “fake news” and evaluat*, all of the articles will mention fake news and all will have a form of the word evaluate—evaluates, evaluating, evaluated, evaluation, evaluations.

If the search is not pulling up enough articles, consider synonyms or near-synonyms for some of the words. In this article, we have seen “alternative facts,” “rumors” and “urban legends” used in place of “fake news.” Use the Boolean operator OR to link these terms, as in: “fake news” OR “urban legend*.” We might as well put a truncation symbol after “legend” to catch both singular and plural forms of the word. We can combine all of these in one search, using parentheses to clarify what is being AND-ed and OR-ed, like this: (“fake news” OR “urban legend*”) AND evaluat*. The resulting articles are likely to be relevant to your search and provide good content for your speech.

When trying to locate facts for speeches, consider adding the word statistics or reviews to your subject search, such as: breast cancer AND statistics or iphone AND reviews. Your audience will give more credence to your point of view if you include objective facts or the views of respected experts in support of your position.

Help your club

Your Toastmasters club may want to explore these topics further. The infographic created by IFLA from a FactCheck.org article “How to Spot Fake News,” is available for download in several languages from the IFLA website.

To learn about the free periodical databases you may be able to access in your community, contact your local library. Why not invite a local librarian to your club to introduce your members to the resources available online? If yours is a corporate club, your company may have its own library and a librarian who is familiar with local resources.

Teresa R. Faust, MLS, CC is library director at the College of Central Florida and a member of the Ocala Noon Toastmasters club.

Previous Article

Previous Article