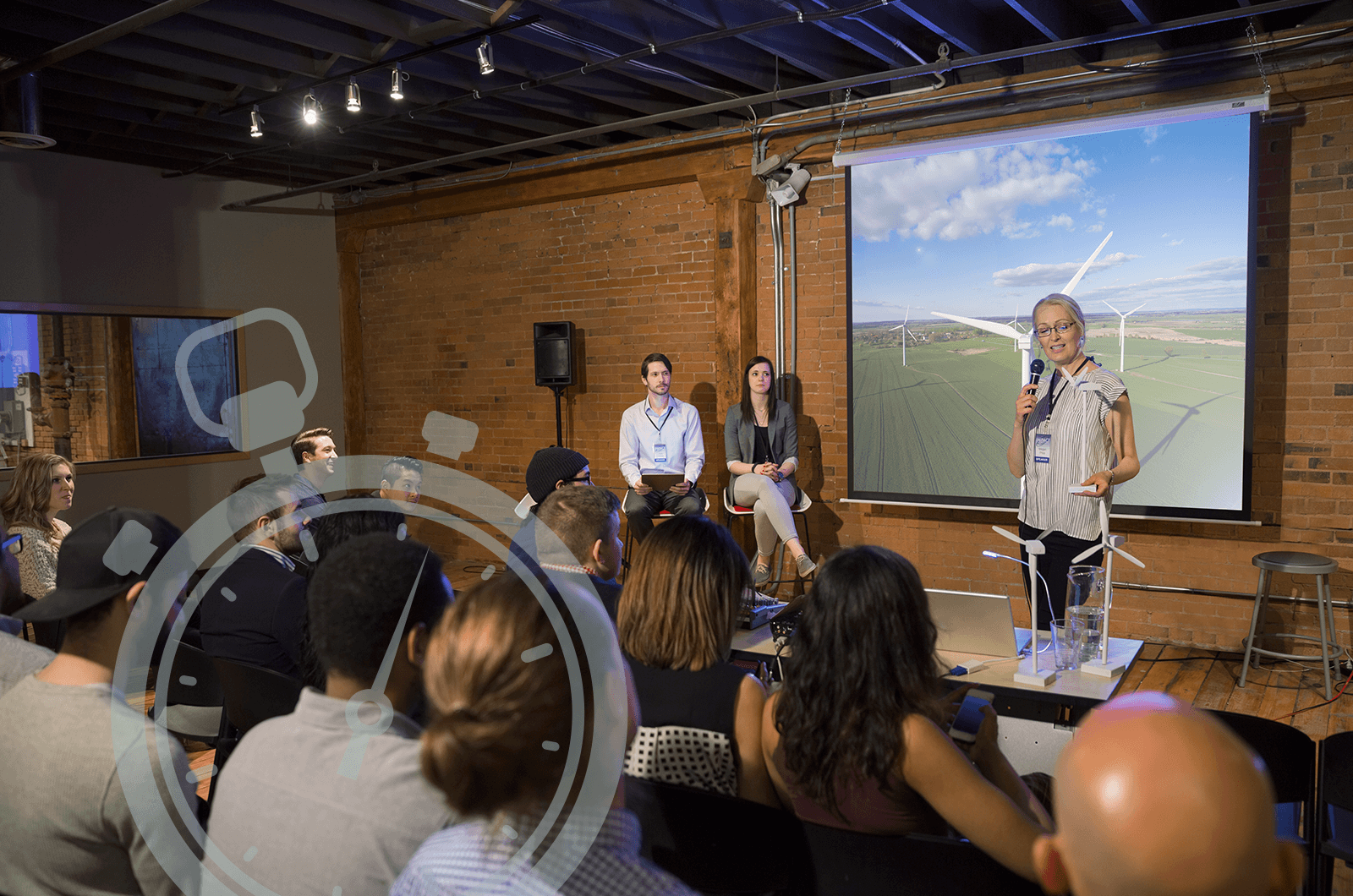

On the surface there might seem to be little redeeming value in a speech that lasts about as long as it takes to retrieve your daily mail, but millions of speakers around the globe would beg to differ. In what continues to be an international phenomenon, presenters are gathering in cities from Beijing to Boston to hone their craft, build community and learn how to “make every word count” by participating in tightly timed presentations known as “Ignite,” “PechaKucha” and “lightning talks.”

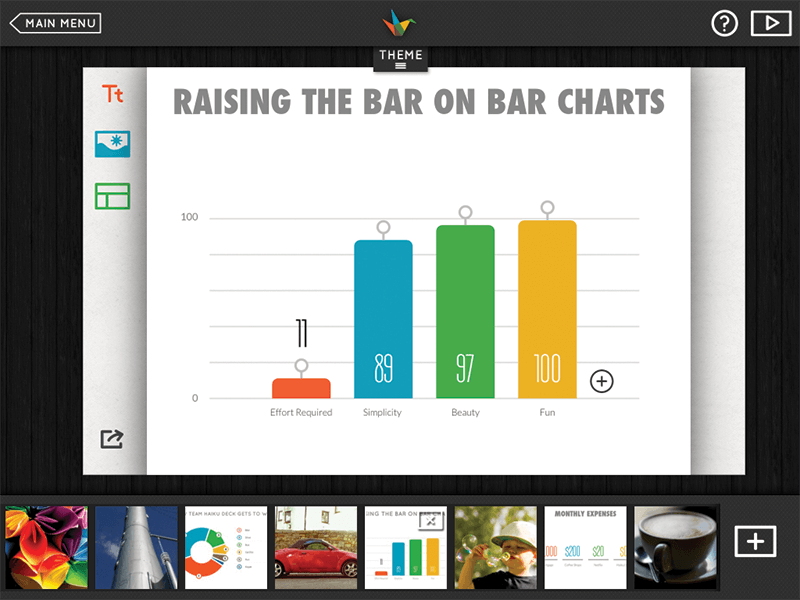

These fast-paced events place presenters on an extreme speaking diet by giving them only five to six minutes to deliver slide-based presentations, allowing 20 slides with just 15 to 20 seconds to address each one. The defining feature of the format is that slides advance automatically outside of the speaker’s control, forcing presenters to refine their messages and delivery approaches in ways they’ve rarely had to do before.

Ignite and PechaKucha (pronounced pe-chak-cha) have a beat-the-clock kind of competition that many find engaging, with audiences often cheering speakers on to meet time limits and post-speaking events that help participants create a sense of community. But the bottom line, according to those who have participated in or coached others preparing for these micro-presentations, is that the format teaches valuable lessons on speaking that can be applied to a variety of communication scenarios, regardless of the time given to speak.

A Movement with Momentum

The movement began in 2003 with the launch of PechaKucha, devised by Tokyo-based architects Astrid Klein and Mark Dytham as a way to give design professionals a more compelling way to present and to increase the number of speakers who could present in one evening. Speakers are given 20 seconds to show each of 20 slides, for a total of six minutes and 40 seconds. PechaKucha (Japanese for “chatter”) grew so popular that by 2016, events were held in more than 1,000 cities worldwide. Each event is hosted by a local organizer and is held in venues like restaurants, bars, private homes, universities, churches and even prisons.

Ignite talks, founded by Brady Forrest and Bre Pettis in Seattle, Washington, use a related format. Ignite events take the concept of PechaKucha a step further by eliminating five seconds of speaking time from each slide, giving speakers just 15 seconds to address each of 20 slides. While that reduction may not seem significant, speakers say it can make a crucial difference in a setting where every second counts.

A third, lesser-known format is the “lightning talk”—a presentation of five to 10 minutes typically used in conference settings, with a multitude of presenters giving their speeches one right after another. Lightning talks are a way for speakers to quickly cover an array of topics or research for audiences with expertise in a given field. Formats can vary, and the use of slides is discouraged in some cases and allowed in other instances (typically, the 20-slide rule applies)—with a caveat that speakers avoid reading directly from them.

“Most audiences wish speeches were shorter, not longer, and that speakers they’re listening to would get [to] the point much faster.”

What Micro-Presentations Can Teach You

Garr Reynolds, a Japan-based presentation skills coach and author of the best-selling book Presentation Zen, has written about the Japanese concept of hara hachi bu, which means “to eat until you’re 80 percent full.” Reynolds believes speakers should apply the concept to presentations as well as to meals, leaving their audiences “satisfied but still hungry for a bit more.” Ignite and PechaKucha, when well-executed, honor that idea.

All these rapid-fire presentation formats have one overriding benefit for speakers, say communication experts. They force presenters to refine messages, content and speaking style to their essence, usually to the benefit of the audience.

“If a person can’t hold your attention for five minutes, why would you want to give them 30 minutes or an hour for a speech?” says Scott Berkun, who coaches Ignite presenters. He has given many Ignite talks himself and is the author of the best-selling book Confessions of a Public Speaker. “A lot of people think they can speak or write well, but this time frame is the ultimate test and constraint. It forces you to distill down exactly what your message is and what you want to communicate, with no fluff or wasted seconds.”

When speakers who have delivered an Ignite or PechaKucha talk return to their Toastmasters clubs or their jobs to prepare longer presentations, notes Berkun, they’ve often built up new muscles for how to edit and reduce messages to their most meaningful core. “And what audience won’t appreciate that?” he asks. “Most audiences wish speeches were shorter, not longer, and that speakers they’re listening to would get [to] the point much faster.”

Berkun says the format helps presenters make their spoken messages stand out, with images playing a supporting role. “Inevitably, in many standard presentations a speaker’s slides—which should be a prop to support or amplify a message—instead become the center of attention and the speaker becomes the prop,” he says.

When coaching Ignite speakers, Berkun suggests a standard slide design isn’t necessary. “Speakers could just project a black background as one option,” he says. “Poorly designed visuals can be distracting, and the other thing Ignite speakers don’t want to do is end up chasing their slides, because they won’t catch up. What they say and how they say it matters most.” Berkun even encourages speakers to put up the same slide twice if they feel they need more time to make a point.

Because slides are only visible for 15 seconds, speakers have to be more “visually concise,” Berkun says. “You can’t use an elaborate flowchart because there isn’t enough time for the audience to process it,” he says. “Ignite teaches about concision in use of visuals as well as in words.”

Michelle Mazur, a speech coach based in Seattle, also has worked with clients to create high-impact Ignite talks. “Ignite forces you to get crystal clear on the message you want audiences to take away from your talk,” Mazur says. “It makes you eliminate anything that is superfluous to your one big idea. I personally love the challenge of achieving that level of clarity and succinctness. Ignite also encourages you to come up with a unique and compelling title for your speech.”

Toastmasters who give Ignite or PechaKucha talks can apply valuable lessons from those experiences to their professional lives, Mazur says, particularly when it comes to presenting to senior leaders in their organizations.

“Those in the C-suite [e.g., chief executive officer, chief financial officer] are often impatient and just want you to cut to the chase and tell them your recommendation or make your pitch,” Mazur says. “Ignite forces you to leave out all the nuanced arguments or justifications and get right down to it. Top executives want presentations that follow a format of ‘very short intro, here are my findings, here is how you can apply them to make the organization better.’”

Ignite and PechaKucha also give Toastmasters an opportunity to get out of their comfort zones, experience a new speaking challenge and be introduced to a new community—often having fun along the way. “It puts you up on a bigger stage than a club setting and pushes the boundaries of your speaking style,” Mazur says.

These short, fast-paced sessions also can help speakers who are faced with presenting large amounts of data transform that information into more digestible and engaging content, says Greg Owen-Boger, vice president of Chicago-based presentation-skills coaching firm Turpin Communication.

“We work with a lot of professionals in information technology, the sciences and health care who often have to communicate a lot of data in presentations,” says Owen-Boger, co-author of the book The Orderly Conversation: Business Presentations Redefined. “We help them trim that content down into just the most crucial and compelling points. Ignite and PechaKucha formats help speakers do much of the same thing.”

Avoiding Pitfalls

If there are drawbacks to these micro-presentation formats, it’s in placing the competition aspect of the talk—beating the clock in slide countdowns—over and above building other communication skills, say speech coaches.

“The danger is putting too much emphasis on the performance and not enough on having a conversation with the audience,” says Owen-Boger. “Speakers work so hard to fit the format, with the audience often cheering them on to get the words out before the slide advances rather than because of the quality of content they’re delivering.

“It creates a lively and fun environment, but there is some question as to what kind of communication goals are being met.”

Berkun says one of the biggest problems new Ignite speakers have is trying to fit too much material into five or six minutes. “Some are under the impression that the higher the density of information, the better the talk will be,” he says. A good Ignite talk, he adds, “may only touch on 20 percent of the information they know.”

“If a person can’t hold your attention for five minutes, why would you want to give them 30 minutes or an hour for a speech?”

—SCOTT BERKUNIgnite speakers also need to understand they don’t need to abandon the power of the pause to accommodate the format. “Within a minute or two of practice sessions, many new Ignite speakers already are out of breath,” Berkun says. “They’ve created no audible ‘white space’ between their sentences. They need to practice breathing when they rehearse, and even consider creating slides designed just for helping them catch up and take a breath.”

Ultimately, events like Ignite, PechaKucha and lightning talks help speakers develop the one skill most audiences around the world want more of—getting to the point as quickly as possible. “With all of these formats, the sooner you establish that you know what good material is, the more attention you’ll have from your audience,” Berkun says. “The same concept holds true for most of the presentations that we all give.”

Dave Zielinski is a freelance writer in Minneapolis, Minnesota, and a frequent contributor to the Toastmaster magazine.

Previous

Previous

TAKING ITS CUE FROM HAIKU

TAKING ITS CUE FROM HAIKU

Previous Article

Previous Article