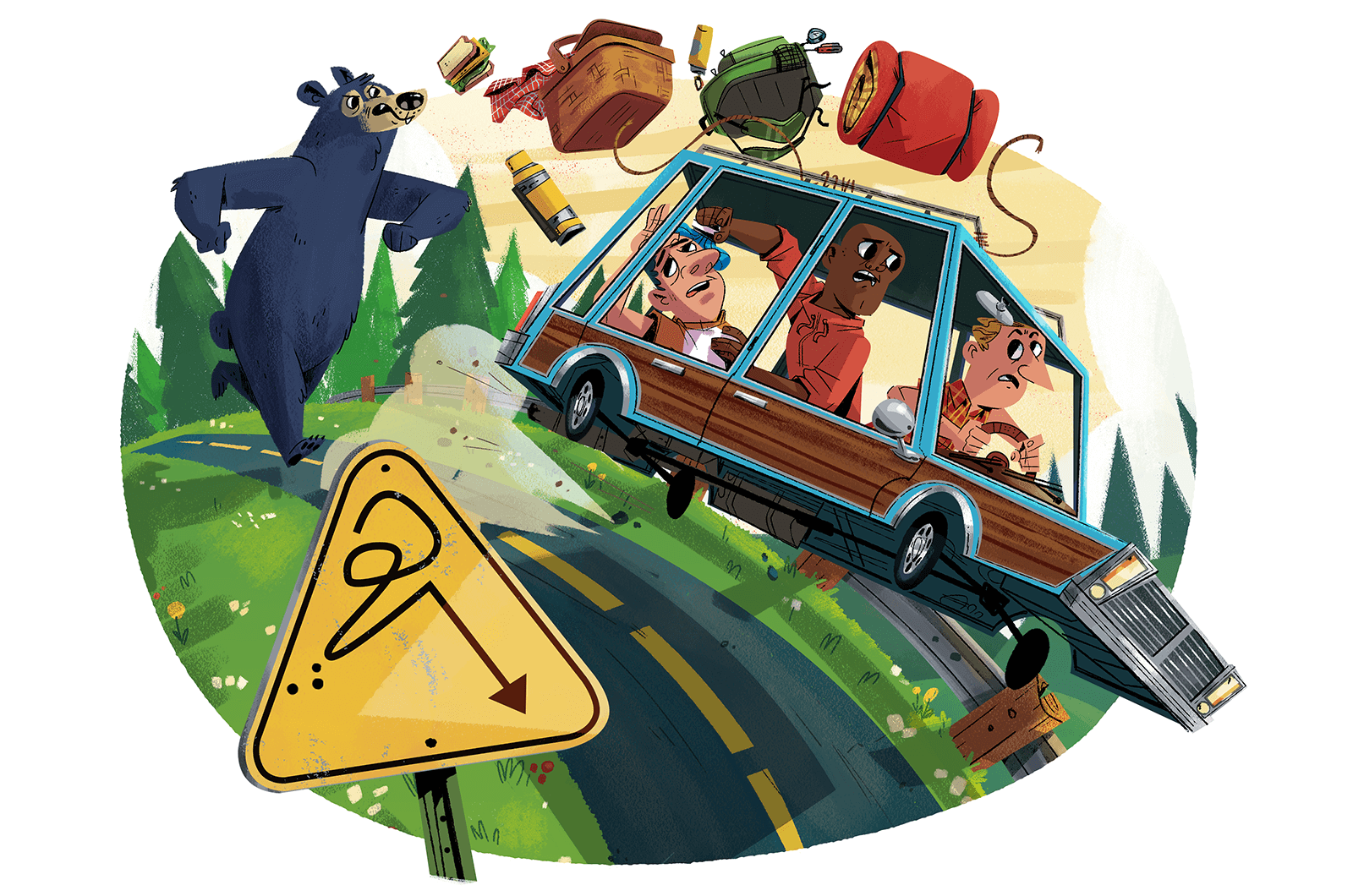

Okay, let’s say you’re taking a nice walk in the woods and a black bear appears about 30 yards up the trail. You are, quite naturally, afraid, causing your body to release pheromones that have a subtle but distinct odor. You can’t notice them, but the bear—having a sense of smell 2,100 times sharper than yours—most certainly does. And fear, to the Ursus americanus olfactory system, smells like a rib-eye steak with sautéed mushrooms and onions. You could run, but you have two legs and he has four. What are your odds? If you freeze, he can still smell the fear, which only means you’re saving him the trouble of chasing his lunch. Or you could wave your arms and yell, which will either scare him off or make him angry. How do you feel about gambling?

Things are looking grim. But wait! You’ve just been to a business leadership conference where a famous management guru gave a lecture on “out of the box” thinking. You weren’t expecting much. Every time you think out of the box, your boss says it’s too far out of the box. But suddenly the famous management guru punctured your apathy with a PowerPoint slide showing the Chinese word for “crisis,” explaining how the word consists of two symbols, one meaning “danger” and the other “opportunity.” Suddenly, you’re wide awake. This is a revelation, an epiphany—a perceived danger containing the possibility of rich reward! What a concept! And here you are, in a crisis, facing danger—the perfect time to prove the truth of this Far Eastern wisdom. Your fear is replaced with that good old entrepreneurial spirit. If there’s an opportunity here, you’re going to take it, so you decide to walk toward the bear, who jumps on you and kills you and you’re dead.

What happened!!?? Well, to put it briefly, you were misinformed. That famous management guru with the best-selling books and the monogrammed laser pointer wasn’t telling you anything new. He wasn’t even telling you the truth. He was simply repeating a gross misunderstanding of Mandarin and other Sinitic languages, which, as Victor H. Mair, a professor of Chinese language and literature at the University of Pennsylvania, points out, has been perpetrated for years by people who want to appear wise when in fact they are displaying complete ignorance. The Chinese, on the other hand, are wise. They know danger when they see it and they don’t pretend it’s anything else. Yes, the Chinese do spell “crisis” with two characters, but they both mean roughly the same thing—Danger! Peril!—just so you get the point.

I use this example to warn our international readers that English, too, has words that are not always what they seem, and in the interest of keeping people from being eaten by a bear, I’ll give a couple of examples. If an English speaker tells you they have some “incredible news,” and if you know, through diligent study of English vocabulary, that “incredible” means “impossible to believe,” you would be well within your rights to say, “Thanks, but I prefer the credible kind.” You are not being a wise guy; you are being etymologically correct.

Another fraught word is “downhill,” which has both a literal meaning—i.e., physically going down a hill—and at least two metaphorical ones. If you say, “It’s all downhill from here,” it means you’ve finished the hardest part of some task and the rest will be easy. On the other hand, if you mention that a friend is “going downhill,” it means the opposite—he or she is in some form of decline, which is anything but easy. So let’s say you’re in a car with a driver and two other passengers, one of whom is critically ill. Cresting the top of a steep incline, the driver says, “We’re going downhill now.” The healthy passenger, feeling the sick passenger’s weakening pulse, says, “He’s going downhill.” And then the sick passenger suddenly recovers, sits up, and says he feels so good “it’s all downhill from here.” At this point it would be perfectly acceptable to say: “Why are you all repeating yourselves?” It would also be understandable if you got out and took a bus.

I hope you get my point. If not, then British children’s author Roald Dahl certainly clears it up with this sagacious advice: “Don’t gobblefunk around with words.” I couldn’t say it any better.

John Cadley is a former advertising copywriter, freelance writer, and musician living in Fayetteville, New York. Learn more at www.cadleys.com.

Previous

Previous

Previous Article

Previous Article