It is December 2022, and I am in the disputed territory of the West Bank, not far from Jerusalem. I am facilitating my first storytelling workshop for Palestinian and Israeli women. Due to government regulations and safety concerns, the private farm where we are located—the headquarters of the local nongovernmental organization sponsoring the workshop—is the only spot in the area where these two warring peoples can meet.

After I tell a story and take the participants through a few trust exercises, an Israeli begins a folktale that she learned as a child from her Russian refugee grandmother. Unfortunately, she can’t recall how it ends.

Fortunately, I have done my homework. I turn to the Palestinians.

“You know this story, don’t you?” I ask. “There’s a popular Palestinian version too, isn’t there?”

They all nod. Then one of them finishes the story, in Arabic.

After her words are translated by the two interpreters, I say, “Well, my work here is done. I can return to the U.S. now.” Everybody laughs. They understand the incredible thing that has just happened. Two supposed enemies told a story together, without even planning to.

A shiver runs down my spine. It is the highlight of my 25-year speaking and storytelling career, and I feel incredibly blessed.

Seeking Peace

My work with the nongovernmental organization Roots/Shorashim/Judur (known simply as Roots) began with a meeting of old friends. I knew Hanan Schlesinger when we were teenagers. When we reconnected 40 years later, he was a rabbi with a long gray beard, living in a Jewish settlement in the West Bank of the Jordan River, on land that is neither fully Israeli nor fully Palestinian. He explained to me that he is a peace activist and the co-founder of the joint Israeli-Palestinian organization, which has a unique outlook.

“Most peace organizations want us to focus on the fact that we are all human,” Rabbi Schlesinger said. “That is to say, that we are all the same. Our differences are the cause of the violence between the two sides, so those differences are minimized. But Roots believed that we have to confront those differences head-on, and grapple with two historical and national identities that contradict and deny each other.

“Only when we learn to respect the other side’s self-understanding and experiences and to trust them, can we move forward in a positive direction toward a lasting peace.”

With my public speaking experience, I felt I could help Israelis and Palestinians develop and use their own speaking skills, as well as bring them together for a shared experience. The organization had already done something similar with photography workshops. Then, after seeing a public presentation about the group’s work and ideals, I was completely hooked. I wanted to get involved.

Because the Roots goal of mutual respect, trust, and connection is what storytelling is all about, the organization’s board approved my proposal. Then COVID intervened. While I waited for permission to travel, we fine-tuned the workshops. In the meantime, I presented an eight-week public speaking/storytelling class online for the organization’s staff.

Moving Forward

Fast-forward to my arrival in the West Bank—several years since I’d first gotten excited about working there. I must admit to having second and third thoughts regarding my ability to accomplish what I’d set out to do. But they soon dissipate. Over the course of the next three weeks, I have the honor of telling and discussing stories with both women and men around the theme of peace. (We hold three workshops for women and one for both women and men.)

Two interpreters translate the participants’ words into English for me, and into Hebrew and Arabic, respectively, for the Israelis and Palestinians. The participants comment on and ask questions about each other’s stories. I hear both folktales and true personal stories on a range of subjects, mostly from women.

One shares her terror on learning that her son had gone on a 40-day hunger strike in an Israeli prison. Another tells how learning the bloody history of the region had caused her to move to the Middle East to reclaim her people’s historic homeland. A third describes needing 100 stitches after being hit by a boulder aimed at her car while driving not far from her home.

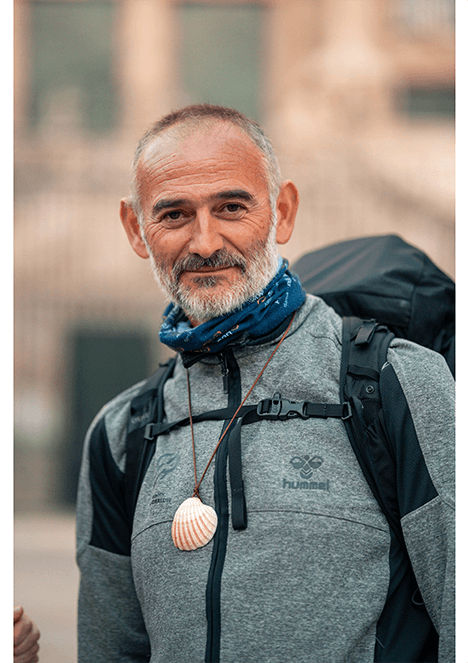

Israeli Liora Hadar uses storytelling to connect with others. Photo Credit: Bruce Shaffer

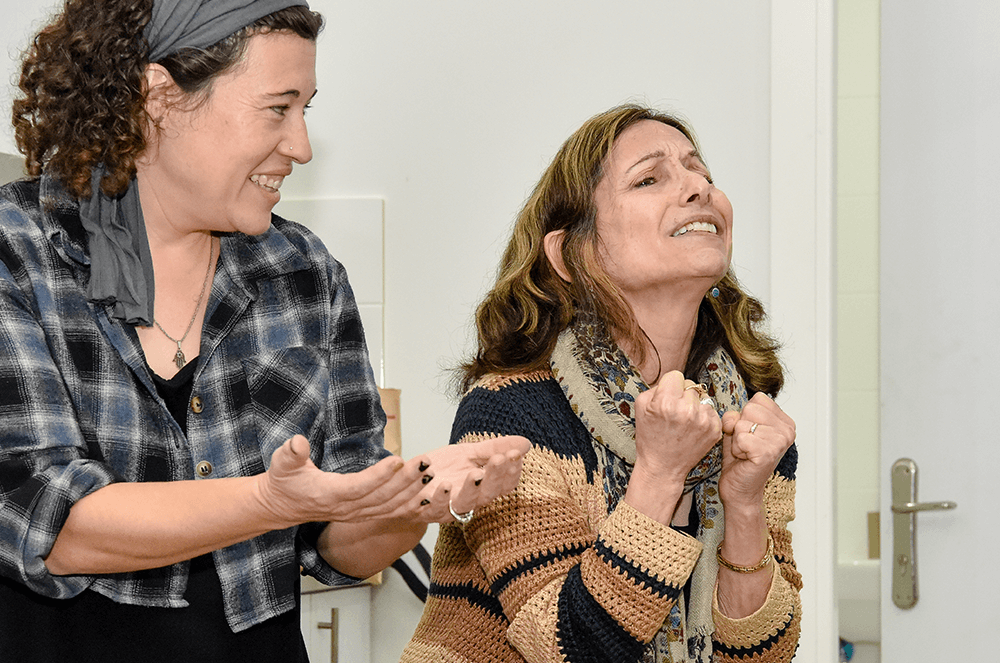

Israeli Liora Hadar uses storytelling to connect with others. Photo Credit: Bruce ShafferIn addition to the storytelling, we engage in improvisational theater techniques to further break down emotional barriers.

Not all of the stories are painful. One woman tells of a childhood fantasy of being on a popular radio program, while another details a perfect birthday. An Israeli talks about how the simple act of greeting Palestinian workers with the traditional words “Ramadan Kareem” during the monthlong Muslim holiday opened an ongoing dialogue with strangers. A Palestinian explains that he became involved with the Roots organization due to the kindness of an Israeli soldier when he was a child.

Naomi Dardik, an Israeli participant in the program, says of the experience, “When we make space to share our stories, we make space for dialogue. Not trying to convince someone of our rightness or to bring them to an opinion, but to relate on a human level of ‘I can understand you, and you can understand me.’”

Last Chapter

At the final workshop, I perform a story that interweaves much of what I have heard throughout my visit, framed by that folktale the two women had told together at our first meeting. Afterward, as we all hug and kiss goodbye, my mind keeps returning to the childhood saying “Sticks and stones may break my bones, but words will never hurt me.” Anyone who is emotionally abused or bullied knows this is not true. Words can hurt. They are powerful enough to change not only another human being, but also the world.

Fortunately, we had used them for good.

“When we listen to others’ stories and share our own … we can, for a few moments, leave our perspectives and biases [behind] and hear someone else’s experience,” says Dardik.

A Palestinian participant named Mousa—who asks to use only his first name for safety reasons—agrees about the importance of listening to the stories of others.

“In the past,” he says, “I was just thinking about getting my story out without caring to listen to other people’s stories. What I found in this workshop was that all the stories have two faces, even those that are not directly related to the Palestinian-Israeli relationship. Someone looks at a story from one side; the other is looking from the other. But we need to understand a story from both sides.” Mousa says he also came away from the experience with an even stronger belief that building bridges is more important than creating obstacles.

Engaging in public speaking and storytelling in the West Bank was a lot more than simply being a “sage on a stage.” It also included helping people understand that this powerful tool of storytelling is available to anybody. It can help people from very different backgrounds come to a place of understanding and respect.

Toastmasters can use their skills apart from traditional public speaking venues in many different ways. Maybe you, too, want to go to a war-torn area and create a safe space for people to sit and listen to each other. Or maybe your work is closer to home, bringing together coworkers, neighbors, or family members through speaking and listening.

“This series changed how I experience the world around me,” Dardik says of the workshops in the West Bank. “The world would be a different place if everyone listened more to each other’s stories.”

I couldn’t have said it better myself.

Caren S. Neile, PhD teaches, writes, and stockpiles social capital in Boca Raton, Florida. Visit her at carenneile.com

Previous

Previous

Previous Article

Previous Article