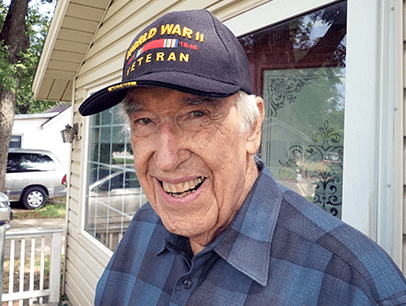

In 1945, Lieutenant Bob King, of the U.S. Army, marched on foot for 285 miles (485 km) over the course of 35 days while carrying the record book of a unique Toastmasters club in his pocket. Dubbed Oflag XIII-B Toastmasters, the club was composed of 15 American prisoners of war (POWs) being held at the Oflag XIII-B camp in Hammelburg, Germany, during World War II. The men had been captured at the Battle of the Bulge in Belgium, in December 1944. They were subsequently sorted by military rank and initially sent to a camp intended for Russian prisoners before being transported via boxcar to the Hammelburg prison camp.

The meeting notes depict the activities of a group of POWs who, amid air raids and limited sustenance, found comfort in structured club meetings, where they shared speeches (and humor) about their lives, learned from each other, and helped ease the burden of life in a military prison camp.

A Club Emerges

Conditions at the camp were demoralizing, with freezing temperatures, a lack of hot water, and insufficient food. Looking for an activity that would provide mental stimulation, King drew on his memories of his father’s Toastmasters club. King, who worked as a game warden in a mountainous and remote area of California prior to the war, frequently joined his father, Elmer King, at his Southwest Toastmasters Club in Los Angeles.

The Oflag club quickly came together and proved to be the perfect respite for the men. They drew up bylaws, which included the agenda and details of the two club officer roles: Toastmaster and executive secretary. Meetings were to be held in the camp library, twice a week for an hour and a half. They would include three impromptu speakers, one six-minute speaker, and one main speaker who would speak for 12 minutes. There were “critics” (speech evaluators) for all speeches, as well as a grammarian and an “evening critic” (General Evaluator).

The first meeting was held February 6, 1945. At the second meeting, on February 9, anticipating that what they were doing might be of historical interest after the war, one member, Chaplain Rowland Koskamp, suggested that the minutes be more expansive and detailed than a mere outline. And in fact, the club proved so popular that within a few weeks, the men voted that any member could bring a guest to the meetings (likely other POWs).

Speech Topics

Topics for the impromptu speakers were chosen by the Toastmaster. Some were seemingly meant to elicit humorous responses, such as “Helping the Little Woman Buy a New Hat,” “How I Handle My Monday Bread Ration,” and “Red Cross Recipes.”

Other topics appear meant to help the men focus on something positive, such as “The Greatest Act of Kindness I Have Seen,” “My Happiest Moment,” “The Most Unforgettable Character I Have Known,” and “What I Shall Do When I First Debark in the U.S.”

The prepared speeches often reflected the men’s interests and occupations prior to the war. An attorney gave the speech “Title and Trust Companies.” Two of the chaplains gave speeches about public speaking. A banker delivered a speech titled “The Federal Home Loan Bank.” Given that the men had no access to reference material and had likely been away from their professions for three years, the choice of topic perhaps reflected their desire to continue to make use of their skills and keep them from atrophying even more.

Other prepared speeches related to the men’s hobbies or interests, such as “My Hobby – Fishing,” “A Fascinating Business – Greyhound Racing,” and “Sunset Symphony.”

POW Realities

The minutes reflect other realities of life in a POW camp. The determined meeting time of 1300 was accompanied by the caveat “air raids and noon soup permitting.” A few weeks later, the time was adjusted to 1230 hours “in an attempt to avoid air raid restrictions.” This referred to the frequent Allied air raids and a strict air alert system that gave the men only a few minutes’ advance warning.

By the third club meeting, the men discussed holding two impromptu talks instead of three to decrease the length of meetings, as the library of Oflag XIII-B was deemed “too cold for long-winded discussion.”

At the end of February, the men decided that the Toastmaster be elected for two meetings regardless of meeting times, “due to difficulties brought by air alerts, Red Cross boxes, and other interruptions common to POW life.”

The notes occasionally reflect humor or inside jokes, indicating a sense of camaraderie and attempts to keep up good spirits. The forward to the meeting records notes: “The club met in the camp library, to the accompaniment of the rattle of empty mess kits, with frequent admonitions to non-existent waiters to be less noisy with dishes.” And on March 13, “Captain Luzzie suggested that coffee might be served at our meetings. The kitchen will be contacted on this matter.”

Topics for the impromptu speakers were seemingly meant to elicit humorous responses, such as “Helping the Little Woman Buy a New Hat,” “How I Handle My Monday Bread Ration,” and “Red Cross Recipes.”

That’s not to say the men didn’t take the club and their speeches seriously. Some of the notes could be from any Toastmasters meeting. At the second meeting, the critic of the evening pointed out the “over-usage of ‘ah,’ slurring of words, lack of animation, and ‘little imagination used thus far by the speakers.’”

The Toastmaster frequently had to remind speakers and critics of time limits, and one critic pointed out the necessity of keeping to one’s subject, a familiar refrain for many Toastmasters.

Critiques included comments on the speaker’s approach to the table, posture, gestures, use of notes, use of hands, subject matter, and general confidence. A common critique was a lack of animation by the speakers, and after a few weeks of this note, one critic of the evening remarked that it was “due perhaps to poor diet.”

As the meetings continued, the critiques and the speeches became more substantive. One evening critic commented that the speakers’ evaluators needed to be more constructive and thorough. Another suggested that the meetings would benefit from more formality.

Visitors were becoming more regular, and the records indicate that minute notes and meeting roles were explained to guests, who were often called upon to introduce themselves.

End of the Club, and the War

The scheduled meeting on March 27, 1945, never happened. Gen. George S. Patton attempted to liberate the Hammelburg camp, but was stopped by several German divisions that were rushed in. Americans suffered heavy casualties, and most prisoners were sent on the 285-mile march to Moosburg, Germany. On April 5, the line of men was bombed by American aircraft at Nuremberg, killing many of the men, including two members of the Oflag Toastmasters club: Captain Feiker and Chaplain Koskamp.

King was often tempted to discard the record book during the long march in order to lighten his gear. The men from Oflag XIII-B, who had been scheduled to be evacuated to Hitler’s hideout as hostages, were instead liberated by Americans or released between April 29 and May 2, 1945.

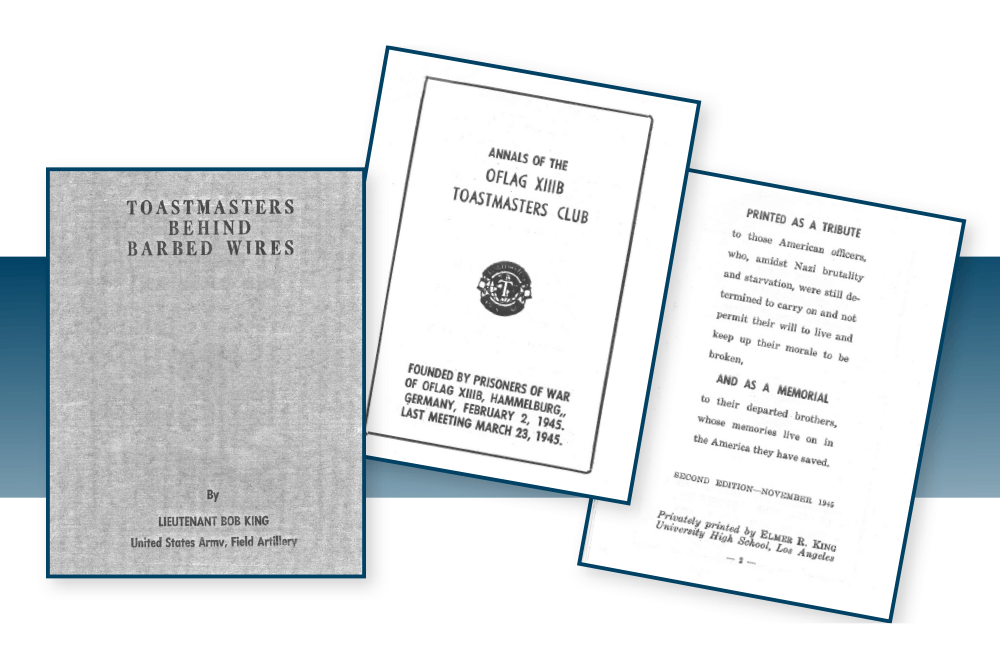

After the war, the minutes of the club were privately printed and distributed by King’s father who titled the pamphlet “Toastmasters Behind Barbed Wires.” He also added a foreword, giving details of how the men came to Hammelburg Oflag XIII-B, and an epilogue explaining the attempted liberation, subsequent long march, and eventual liberation.

Despite lasting only a couple of months, the Oflag XIII-B Toastmasters Club is a poignant reminder of the many ways that Toastmasters can provide purpose and community. Even in the harshest of conditions, Toastmasters has the ability to change lives.

Previous

Previous

Previous Article

Previous Article