"You’re doing it again. You’re talking over our heads.” My friend Peg said this to me frequently. In the 1980s and 1990s, I was an aircraft engine researcher for the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA). Aircraft engines and rocket engines use the same thermodynamic principles, so I can say with guarded certainty, “I’m a rocket scientist.”

Maureen Zappala

Maureen ZappalaHowever, I often forgot that my friends didn’t know rocket science. Apparently, by Peg’s frequent observation, I had a bad habit of slipping techy-talk into my conversations, completely unaware that I was confusing and boring my friends. I was an awful science communicator.

These days, we are surrounded by science news. The proliferation of new discoveries, and the implications for people’s daily and future lives, now fill mainstream conversations and the mass media. Through countless blogs, websites, news stories, and stunning photos, the point seems to be: Science is never boring. However, it’s often presented that way.

As a result, a new emphasis on plain speaking has emerged as more scientists and technical experts must describe their work to nonscientists clearly, accurately, and most of all, engagingly.

Aniruddha Dutta

Aniruddha DuttaAniruddha Dutta, a former Toastmaster in Germany and a Ph.D. student in metal physics, has used cream-filled cookies and leftover food to demonstrate his scientific concepts to audiences. Thinking of his mother helps Dutta assess the simplicity of his speeches. “I always ask myself, ‘How can I explain this to my mom,’ who is a classical vocalist?” he says. (Read more about Dutta in the sidebar, A Grand Slam.)

Humor and persuasion also help in appealing to diverse audiences, such as the media, consumers, corporations, grant-making entities, venture capitalists, and policy makers.

Why Explain Science?

Your life constantly intersects with science. Have you flown in a plane, used a remote device, talked to your car, or cooked a meal? That’s science disguised as an everyday life activity. You may not know the how or why—but you appreciate that it’s there and that it works.

Allison Coffin, Ph.D., DTM, an associate professor of neuroscience at Washington State University Vancouver, is a passionate believer in science and how it matters in the world. Her expertise is in studying hearing-enabling hair cells in fish, in the hopes of developing technologies or medications to prevent hearing loss in humans.

Allison Coffin

Allison CoffinCoffin joined Metropolitan Toastmasters in St. Paul, Minnesota, U.S., years ago to practice defending her master’s thesis. She believes so strongly in the power of communication that she co-founded Science Talk, a nonprofit organization that convenes an annual conference to train scientists in making influential, effective presentations. The Science Talk website offers an invitation to action: “There’s a revolution in science right now—the idea that scientists should sometimes leave the lab and talk about what we do, and why we do it, to real people.”

That’s because science and its applications have countless implications for society.

“In major issues, it’s not just about the science,” Coffin says. “There are business interests, local municipal interests, and natural resource interests. Just saying ‘here’s the science’ won’t work. But when science can be part of the conversation, and we build relationships first, it’s easier to sell another person on the ideas.”

Coffin is a founding member of her current club, Salmon Toastmasters in Vancouver, Washington, U.S., and has belonged to numerous other Toastmasters clubs over the years.

Expertise Is the Easy Part.

While stellar public speaking talents are in demand among technical professionals, that doesn’t mean techies take to addressing general audiences naturally. In fact, the “curse of knowledge” can be a huge communication roadblock for an expert who knows a topic so well they can’t deconstruct big-picture knowledge to levels that lay audiences understand.

Dialogue, especially your own internal dialogue, can turn science into story, and makes you seem more relatable to your audience.

In the July 2015 issue of Toastmaster magazine, engineering consultant Carl Rentschler, in his article “Communication Challenges of a Techie,” reflects on why technical people like himself might struggle with verbal communication. For example, he describes scientists who don’t realize they lack strong communication skills and assume that their technical strengths will communicate the significance of their work. “I have heard atrocious speeches by technical people and frankly, they seem oblivious to the fact they are not getting through,” he writes.

How a Science Speech can Teach.

If you are a scientist and a Toastmaster, you’ve probably delivered a few science speeches in your club or to an audience of nonscientists. Understanding even more about the unique principles of science communication can help you have more impact with your words.

A well-delivered scientific explanation that uses clear language can comfort, inspire, and empower nonscience audiences. Learning about a medical diagnosis, or a solar eclipse, or why mixing some household cleaners is dangerous, makes people feel competent, secure, and smart.

Perhaps most importantly, clear science communication makes technical information “spreadable”: Jargon-free journal articles are cited more often; uncomplicated talks are better remembered; and straightforward science communication can provide more inclusive cross-topic collaboration between science organizations.

Master Three Elements.

Clear science communication uses a skilled mix of content, structure, and delivery. Toastmasters training helps scientists with all three.

Content is the scientific information you are presenting. Avoid using scientific jargon or industry-specific phrases. Even the same phrases can mean different things to different scientists. When speaking to nonscientists, resist including every detail. Stick to general principles or overviews. Use analogies and metaphors, and include humor if you can.

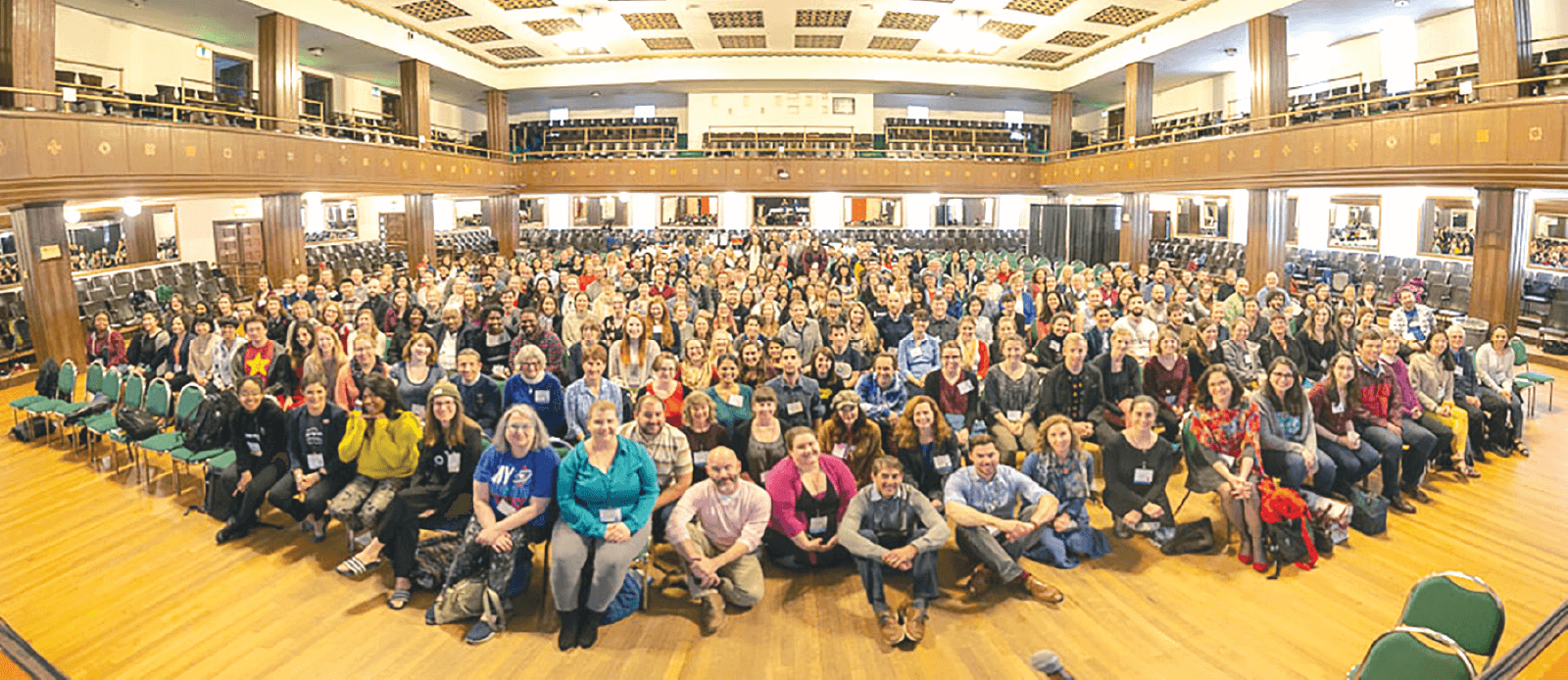

Science Talk 2019, held last April in Portland, Oregon, drew scientists eager to promote best practices in talking about their work with lay audiences. The annual meeting is the brainchild of Toastmaster scientist Allison Coffin and colleagues.

Science Talk 2019, held last April in Portland, Oregon, drew scientists eager to promote best practices in talking about their work with lay audiences. The annual meeting is the brainchild of Toastmaster scientist Allison Coffin and colleagues.Structure is how the content is organized. Shape your presentation on the logical sequence of the scientific method: Determine your problem, hypothesis, method, results, and conclusion. Develop an outline to keep you on track. Use smooth transitions and summarize at the end.

Delivery includes vocal variety, body language, visuals, eye contact, etc. Use your Toastmasters club to practice these elements. Record yourself on video and watch the recording. Practice using any props or slides, so you are comfortable with them.

Bring Science to Life.

Audiences crave a great presentation. As you share your story, consider describing the roadblocks and victories you experienced along the way. “While I was researching this, I discovered …” or “I was shocked when I saw this, and I said to myself …” Dialogue, especially your own internal dialogue, can turn science into story, and makes you seem more relatable to your audience.

Patricia Fripp, a onetime Toastmaster and now an award-winning speaker and coach whose clients include engineers and technical professionals, has additional language advice for science speakers. Her training outlines “skinny” and “fat” language, two terms that relate directly to the quality of science communication. Skinny language is very detailed while fat language is broad and inclusive.

“The challenge for scientists who want to explain or sell their ideas to people who don’t understand the science is to use ‘fat’ language and include abstract concepts and broader terms. They [should] tell the story of how their ideas relate to and affect an individual person, their life, their society, and the world in general. Increasing levels of abstraction require broader language, not the nitty-gritty specifics,” she explains, adding that it’s important to relate the story using words that are familiar or create a visual image in the mind of the listener.

If your goal is to communicate well, it could be worth it to sacrifice some precision for connection with the audience.

Analogies and metaphors help bridge the gap between what is known and unknown. The audience grasps a new concept by comparing it to something they already know. They learn at a deeper level, and retention is much higher. Science-based TED speakers regularly use analogies and metaphors since most of their audience members are not scientists.

Some scientists may be reluctant to use metaphors because they are oversimplified or not entirely accurate. For example, the “ozone hole” isn’t really a hole. It’s a decrease in ozone density. A plane is powered by its engine the same way an inflated untied balloon flies when you let go of it—sort of. These comparisons aren’t totally accurate, but they represent the general idea, and help listeners understand. If your goal is to communicate well, it could be worth it to sacrifice some precision for connection with the audience.

Why Does this Matter to Me?

Maybe you’re thinking, “I’m not a scientist. This information does not pertain to me.” Consider how your life has been improved through science and tell a story about it.

You can be an ambassador for science, even if you are not a scientist or engineer.

And if you run into my friend Peg, tell her your science story in simpler words. I know I will.

Maureen Zappala, DTM, AS is a former NASA propulsion engineer. Today she’s a professional speaker, author and presentation skills coach, as well as founder of High Altitude Strategies, a coaching and speaking service. Visit her website to learn more.

Related Articles

Presentation Skills

25 Ways to Nail Your Workplace Presentation

Presentation Skills

Previous

Previous

A Grand Slam

A Grand Slam

Previous Article

Previous Article