In May 1944, a teenaged Elie Wiesel was taken to the Auschwitz death camp by the Nazis. It was one in a string of hellish Holocaust experiences the author and human rights activist would go on to chronicle in his book Night.

Nearly 55 years later, in April 1999, Wiesel stood in the majestic East Room of the White House, in Washington, D.C., and delivered a memorable speech titled “The Perils of Indifference.” The 21-minute talk, like other great speeches aimed at advancing the cause of human rights, was marked by passion, power, and purpose.

Wiesel decried the apathy shown by many people and governments during the Holocaust. He pointed to the infamous June 1939 episode when United States President Franklin D. Roosevelt turned away the German ocean liner St. Louis and its nearly 1,000 Jewish refugees, many of whom would perish in the Holocaust. And he credited, and expressed profound gratitude for, those with the courage and moral clarity to act, including the “Righteous Gentiles”—Christians who risked their own lives to shield Jews from peril.

He also cited a long list of dark and deeply troubling chapters in the annals of 20th century history aside from the Holocaust: two world wars, countless civil wars, and assassinations, “bloodbaths” in places like Cambodia, Nigeria, Rwanda, Pakistan, and Kosovo.

Wiesel condemned the attitude of indifference that allows people to stand idly by, or to turn away, when others around them are the victims of cruelty. He tried to understand this regrettable—but common—psychological response:

Of course, indifference can be tempting—more than that, seductive. It is so much easier to look away from victims. It is so much easier to avoid such rude interruptions to our work, our dreams, our hopes. It is, after all, awkward, troublesome, to be involved in another person’s pain and despair. Yet, for the person who is indifferent, his or her neighbor are of no consequence. … Their hidden or even visible anguish is of no interest. Indifference reduces the other to an abstraction.

Indira Gandhi challenged an entrenched traditional value system that had long relegated Indian women to a far lesser role.

He posited that such apathy, more than hatred or anger, is what “makes the human being inhuman.”

Wiesel, who was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1986 and died in 2016, spoke from a sense of personal pain and loss that was deeper than most could know. He spoke in a calm, measured cadence, with effective pauses throughout, but his words resonated with intensity and authority. And there was a call to action that no listener could ignore: Do not stand by in the face of human suffering. Never allow yourself to become indifferent.

India’s Challenge

The same qualities of passion, power, and purpose characterized a stirring 1974 speech by Indira Gandhi. She served as India’s first female prime minister, from 1966 to 1977, and again from 1980 until she was assassinated in 1984.

The title of the speech was “What Educated Women Can Do.” Gandhi delivered it at the 50-year anniversary celebration of Indraprastha College for Women in Delhi. In sharing her vision of how college-educated women could enrich India’s future, she boldly challenged an entrenched traditional value system that had long relegated Indian women to a far lesser role. She believed educated women would fill a critical niche in promoting the nation’s progress:

For India to become what we want it to become, with a modern, rational society and firmly based on what is good in our ancient tradition and in our soil, for this we have to have a thinking public, thinking young women. … I hope that all of you who have this great advantage of education … will make your own contribution to creating peace and harmony, to bringing beauty in the lives of our people and our country. I think this is the special responsibility of the women of India.

In a March 2020 Toastmaster magazine article marking International Women’s Day, Toastmaster Sudarshan Seshadri praised Gandhi’s speechmaking:

“Her speeches were very eloquent, erudite, and effective,” says Seshadri, a resident of Dubai, United Arab Emirates. “She used to attack the nub of the issue directly without an iota of doubt on where she stood on the issue being discussed. She was unequivocal in her speeches, and her speeches were defined by her courage, conviction, and clarity.”

A Defining Moment

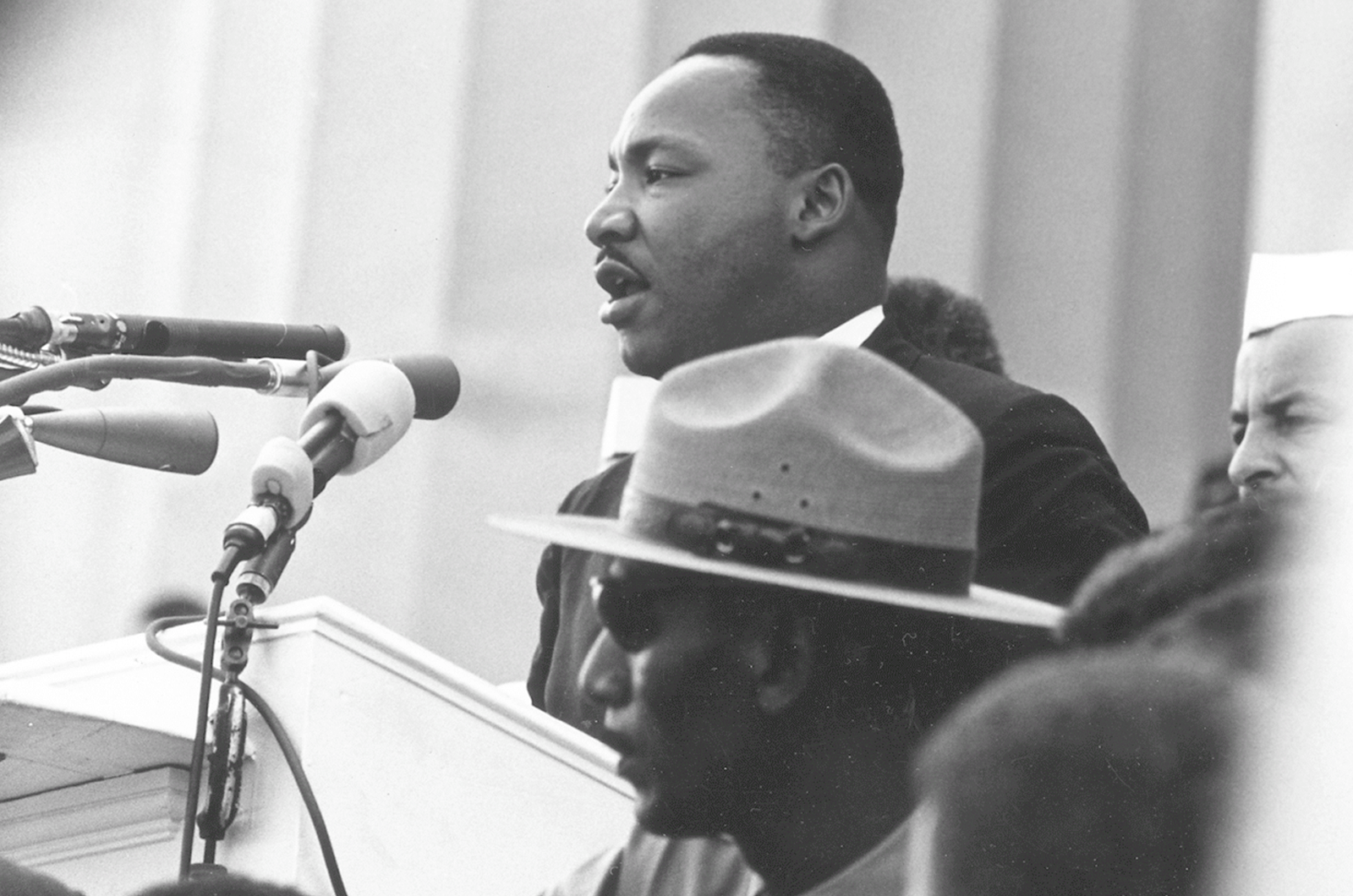

Inspirational speeches often imbue us with a dream, a vision. Perhaps no orator in modern history has done this better than American civil rights leader Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

King delivered his iconic “I Have a Dream” speech on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C., on August 28, 1963. A quarter of a million people had gathered for the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. Many in the packed crowd wore their Sunday finest—suits, ties, hats—despite the sweltering heat. The speech was a defining moment in the American civil rights movement. It continues to inspire millions around the globe thanks to its simple eloquence.

In a part of the speech that was actually improvised, based on past sermons King had given, he declared in his ringing voice, “I have a dream my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character.”

King deftly employed repetition as a rhetorical device. He rhythmically repeated the sentence “I have a dream” several times to start a new paragraph, strengthening the statement’s impact.

King’s six-minute talk contained echoes of the U.S. Declaration of Independence, of American folk songs, even of Shakespeare.

The setting of King’s speech was richly symbolic: It was President Abraham Lincoln who had freed the slaves a century earlier. King invoked Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address (which began “Fourscore and seven years ago”) in his opening:

Fivescore years ago, a great American, in whose symbolic shadow we stand today, signed the Emancipation Proclamation. This momentous decree came as a great beacon light of hope to millions of Negro slaves who had been seared in the flames of withering injustice.

King’s six-minute talk contained echoes, too, of the U.S. Declaration of Independence, of American folk songs, even of Shakespeare. Perhaps most moving were its many biblical allusions and references, drawing on language and themes from the Book of Exodus and the prophets.

Former New York Times literary critic Michiko Kakutani penned a brilliant analysis of the speech in 2013, on its 50th anniversary. She wrote:

“He began slowly, with magisterial gravity, talking about what it was to be black in America in 1963 and the ‘shameful condition’ of race relations a hundred years after the Emancipation Proclamation. Unlike many of the day’s previous speakers, he did not talk about particular bills before Congress or the marchers’ demands. Instead, he situated the civil rights movement within the broader landscape of history—time past, present, and future—and within the timeless vistas of Scripture.”

King’s speech helped bring about the 1964 Civil Rights Act, a U.S. law banning discrimination based on race, color, religion, sex, or national origin.

Wiesel, Gandhi, King—all three knew how to deliver powerful, passionate words in the service of a noble purpose: promoting basic human rights, both for their own communities and for people around the world.

Mitch Mirkin is a member and past president of Randallstown Network Toastmasters in Baltimore, Maryland. He works as a communicator for the research program of the United States Department of Veterans Affairs.

Previous

Previous

Previous Article

Previous Article