Would you like to give a speech without notes, or at least with very few notes? Memorizing your speech word for word is not only difficult, it can result in a stilted style or in completely forgetting what you are going to say. While it is a good idea to memorize your first sentence or two, and your last—to tie down the ends of your speech—memorizing a speech word for word rarely is worth the effort.

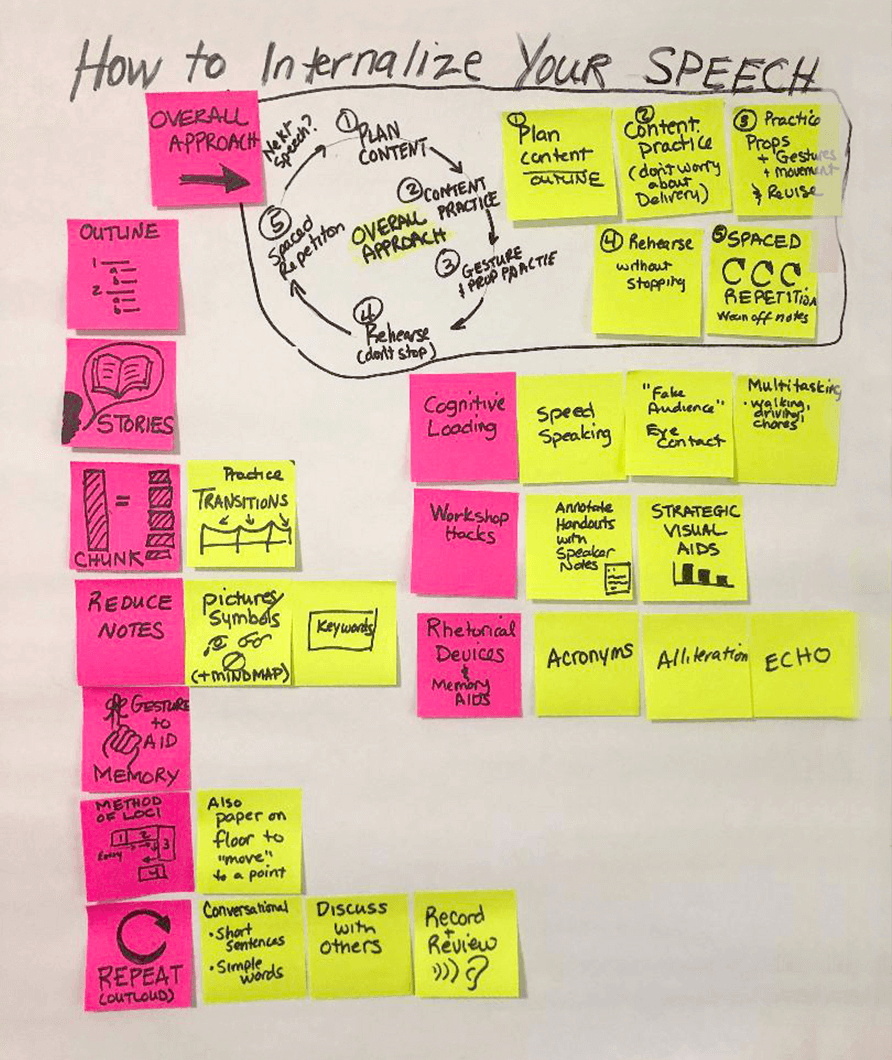

As a professional speaker and presentation coach, I tell my clients, “Don’t memorize. Internalize.” I first heard that phrase years ago from the 2001 World Champion of Public Speaking, Darren LaCroix. Internalizing a speech works well for most people as a three-step process. Step 1: Create memorable content. Step 2: Practice the content without being concerned about delivery. Step 3: Incorporate gestures and space out your practice.

1 Create Memorable Content

Structure Your Speech Logically.

How you organize and develop your content can enhance your recall. Think of your speech like a tree, with the main message being the trunk. Then brainstorm subpoints (the branches of the tree) and supporting material, such as stories and data (the leaves of the tree). Finally, get out those pruning shears and eliminate the branches and leaves that do not support your main message. This makes your speech more structurally sound, and easier to remember.

Then, create an outline using a logical organizational structure (e.g., topical, compare/contrast, chronological, cause/effect, problem-cause-solution). An alternative is a mind map, a diagram for visually organizing your ideas and information, linking items around your main message.

Illustrate With Stories.

Stories are concrete and memorable. Relevant stories help audiences remember your points, and help you remember your points too. A story runs like a movie in your mind. When comparing people’s memories for words with their memories for pictures, research has shown significantly superior memory for pictures, primarily due to the greater amount of sensory details associated with the picture. See it. Feel it. Remember it.

Write It Out.

If you have a logical structure with supporting material, writing out your speech will help you create flow, with one idea or part transitioning to the next in a manner that is both pleasing to the ear and memory-enhancing.

Such memory-boosting techniques include:

- Repeat. Repeat phrases using parallel sentence construction, especially in groupings of three. For example: When I was a teenager, I worried about three things: bad people, bad food, and bad breath. Here, the repeated word is “bad,” and the structure is the same for each use (adjective/noun).

- Transitional phrases. Transitions bridge the gap between concepts, helping your speech flow smoothly from one part to the next. A transition also can be a simple signpost such as “first . . . second . . . third.” Better signposting echoes previous material in your speech. So, instead of just saying, “Second . . .” it is better to say, “The second reason is . . .”

- Acronyms. Acronyms use a simple formula of a letter to represent each word or phrase that needs to be remembered. If you have three to five supporting points, you can sometimes create an acronym. For example, in a speech on conflict resolution, you could tell people to LEAP into conflict: Listen, Empathize, Agree, and Partner.

- Alliteration. Alliteration is the repetition of an initial stressed consonant sound, as in “Peter Piper picked a peck of pickled peppers.” Alliteration in excess can be distracting, but in small doses it can enhance memory. For instance, in a speech about persuasive presentations, you could say, “Persuasive presentations begin with three P’s: Pep, Promise, and Path.”

2 Practice Content, Not Delivery

Repeat.

Read your speech a few times out loud. Listen to a recording of yourself. Revise.

Chunk.

Chunk the content and practice parts of it (for example: chunk the introduction, then the first point, second point, third point, conclusion). Include transition statements that occur before and after each chunk.

- Read each chunk aloud, along with transition statements.

- Recall/try to say the chunk without peeking at the written speech.

- Check to see how accurate you are by reading again.

- Repeat until you feel comfortable with the first chunk, and then move onto another part.

Use Keywords.

Reduce your notes to keywords (no more than three to four per sentence). Stories may only need a trigger phrase, such as “Family Christmas Party.” In subsequent practice sessions, reduce your keywords until you have only one (or fewer) per paragraph. “Family Christmas Party” reduces to “Party.”

Use Picture and Symbol Notes.

If your brain remembers better in pictures or symbols, use those instead. While pictures and symbols can take longer to construct, they can quickly connect your brain to your content. As with keywords, you can reduce your pictures to one per point, and then visualize those pictures as you speak.

Discuss With Others.

Discussing your content with others will force you to speak conversationally, be clear, and say things a little differently each time.

Try the Method of “Loci”(also known as a memory journey).

Assign parts of your speech to different physical objects on a path and then practice those parts as you walk the path. In your home, you might give your introduction at the front door, make point one at the refrigerator, point two at the stove, point three at the sink, and give the conclusion at the dining room table. This helps you visualize the journey as you give your speech.

3 Use Props and Gestures to Help Internalize Structure

Move with Props.

Movement combined with props can make a speech unforgettable for both you and the audience. Your interaction with the prop, even just holding up a picture, makes your presentation more concrete, and can add emotion, drama, and meaning to your words.

Gesture to Connect Content With Memory.

Numerous studies have shown a positive effect of using gestures to encode memories, retrieve memories, and decode information for the listener. Spontaneous, unplanned gestures can enhance your fluency, and specific, defining gestures can enhance memory. (A note of caution: Gestures, even if planned, must flow naturally as you speak. Practice and record yourself.)

For instance, if I am making three points about public speaking, I might have these points and the following gestures:

- Focus on your audience. For example, gesture as if looking through a circle formed by a curved thumb and fingers.

- Internalize your material. Try a gesture such as patting your upper chest.

- Tell a story. Gesture by holding your hands like an open book.

More Ways to Enhance Recall

Spaced Repetition.

Trying to cram in your practice right before you give a speech is more time-consuming than spacing out your practice. Spaced repetition (or distributed practice) increases retention better than massed practice (aka “cramming”). How much you space out your repeated practice depends on how much time you have before you give your speech, and if you will be giving the speech again. If you will be giving the speech again, you may want to practice it weekly, and then monthly.

Just Sleep on It!

Long-term memory formation is a major function of sleep. A good night’s sleep can help you cement your speech in your mind. Conversely, if you are sleep-deprived when you are trying to learn (or deliver) your speech, you can’t focus your attention optimally.

Diane Windingland, DTM is a presentation coach from Spring, Texas, and a member of Frankly Speaking Toastmasters in Spring, Texas, and PowerTalk Toastmasters in Minnesota. Learn more at virtualspeechcoach.com. She is also the author of the book The Clarity Code: How to Communicate Complex Ideas with Simplicity and Power.

Related Articles

Presentation Skills

How to Deliver a Speech … Without Notes

Presentation Skills

Speaking Without Notes

Presentation Skills

Previous

Previous

Previous Article

Previous Article